A knock at the door informs me that the postman has a parcel for me. I pull the door wide. “Hiya,” he says, straight-faced, as he hands me the box. I smile inwardly, noting how much I’ll miss this comically cheery variation on “hello” that the Scots elicit by default. I nod and respond, “Cheers” with a soft “r” in the Scottish way. Most of the time I hesitate to practice the accent; trying to pronounce the dialect as the natives do can inadvertently resemble mockery to the uninitiated ear. But this pair of pleasantries are common enough to feel natural, and if the transaction ends there, I fancy I may even pass as a native.

It’s time to head to class so I change out of my lounge clothes and begin the layering process. Socks go on first, then a pair of long underwear and jeans. A t-shirt comes next, followed by a sweater that, along with the wool-lined jacket, I can peel off on arrival. Easy on/off layers are essential for temperature moderation in arctic climates with balmy interior spaces. I finish my apparel off with a pair of ear muffs and the the ever-essential scarf. You are as good as naked in Britain without a scarf. Keeping warm is 15% conventional clothing, and 85% scarf. Or so it seemed to me when I forgot mine once.

Properly insulated, I exit my home and stroll through a small cluster of quiet cobblestone cottages that share my lot. A fading plaque on a neighbor’s exterior wall ironically declares our charming little villa had a past life as a leper colony. The dichotomy summons an Eddie-Izzard-ism to mind: “I grew up in Europe,” he said, “where the history comes from.” The complex is encircled by a short drystone wall, so I stroll to the south-west corner and exit by the driveway onto the sidewalk hugging the street. But just around the cornerstone of the complex, a dirt trail cuts a beeline for the beach, and a footpath by which I can walk with the eternal horizon to one side and the panorama of St. Andrews on the other.

The sea presents a different face every time I traverse this path, sometimes beating its fearsome fists into the retaining wall that lines the cove like an angry god scorning containment, other times lapping listlessly at the sandy shore, as quietly as a cat at the water dish. This afternoon, the tide is so far out that the terrain seems to have tripled in size, a great yawning stretch of solid ground having materialized out of a space entirely occupied by an ocean just a short while before. The earthen landscape changes with each reappearance, as the waters deliver new offerings on every visit, like a charitable caller. By evening, every visible rock, shell and grain will be swallowed again beneath a veil of impenetrable blue.

To my left I pass a playground and sprawling mounds of emerald green grass dappled by grazing wild rabbits. They lope along languidly, parting before me like a fuzzy brown sea as my path turns back into town. A host of fishing boats list stoically in the small harbor beyond, augmented by a romantic backdrop of medieval stone walls and cathedral spires. It looks like a fictional landscape sprung straight from the pages of a haunting fairy tale – no wonder Scotland is full of them.

I cross a short bridge and follow a stone staircase that rises to a road overlooking the north bay and the relics of St Andrews castle. A plaque at this site explains the sordid history of the town’s infamous namesake. Another describes the hanging of a man from the tranquil arched window of the crumbling castle, through which a pensive tourist is presently framed. There’s nothing like a ~nine hundred year old settlement for contrary transpositions.

Fifteen minutes after exiting my cottage door, I arrive at the department for my major; a solitary stone edifice that looks every bit the imposing castle that the genuine article down the road used to be, if not quite as sprawling. St. Andrews is full of these, as though the castle were partitioned off and distributed across the town. I pass through an iron gate, jaunt up the steps and enter by the modestly castle-sized door. The exterior causes the interior to come as something of a surprise, with contemporary white plaster walls, but the wooden banister tracing a curling staircase somewhat redeems it. I follow this up to the second story and meet with a series of white painted doors lining a nondescript hallway, my footfalls on the wooden stair echoing loudly in the noiseless corridor.

The glass doorknob to my left gives way to a narrow room with a high ceiling, framing a long table with chairs all around. A tall bay window at the far end captures an appropriately pensive view of the perennial sea and its secrets. I doff my top layers, draping them over the back of my chair, and seat myself at my professor’s left hand. This is one of my favorite things about my study abroad experience; classes in our department rarely exceed fifteen in enrollment, and I relish the equalizing and intimate setting this allows the administration to cultivate. Speaking across a table makes me feel much more a part of the conversation than enmeshing myself in stadium seating for the oversized lectures I’ve been accustomed to.

After class, I cross a quiet, tree-lined street and turn down a sort of alley-way that cuts between buildings, generally and accurately described as a “close”. This one is uncommonly wide, however, and is referred to as a “wynd”, which Wikipedia defines as a public thoroughfare of antiquity, wide enough to accommodate horses and buggy. Closes and wynds are one of my favorite aspects of Britain in general, being broadly exclusive to foot traffic, and permitting pedestrians a brief refuge from the blare and tumult of the motorized sort. Some paths, such as this one, connect parallel roads, but the entire country is generously infused with an intricate web of walking paths, so that the intrepid explorer can largely steer clear of roaring engines spewing exhaust and stick to the fresh air and silent repose of the scenery. These paths are customarily so narrow and subtly carved between structures as to be easily overlooked unless one knows to be looking. More than once I wandered timidly down a subtle path on what appeared to be somebody’s property, only to be reassured when it carried me well beyond their perimeter. More than once I also doubled back upon landing at somebody’s doorstep.

My favorite such excursion in St. Andrews was known as Lade Braes, and became my sanctuary from the rigorous frenzy of a new school year in a strange land. The population of the tiny town more than doubled in size as parents and their progeny swarmed the streets, and the chaos of getting registered and established, compounded by the unfamiliar territory and protocols, had my nerves at attention for days. But then I discovered the secret of Lade Braes and its quietly meandering path, allowing one to explore the lay of the land from a vantage point both intimately intertwined and eerily detached from its setting. I tried on several occasions to follow it to its end, little realizing that it wound across counties. But the catharsis I found in its natural beauty could not be quenched.

For now, however, I am content to head into town. The wynd I am walking is cobblestone, and intersects with the main road which is paved in the same. It hosts a large fountain as its centerpiece, and the cars make a stuttering rumble as they pass. Most streets in St Andrews are paved with asphalt, so I suspect that the stones here are intended to restrain vehicular traffic to a snail’s pace by its tooth-chattering tempo. Pedestrians roam the roadway in this spot rather freely.

I pass by a plethora of pubs, which may arguably beat even walking paths as the jewel of British lifestyle. I adore a proper British pub, and they have ruined me for public venues in the states. The standard eatery in the U.S., whether it calls itself a coffee shop, a bar, or blasphemously fancies it feigns any right to the title of “pub”, is traditionally furnished with plastic benches or chairs around generic tables in a largely undecorated square box. The true pub atmosphere, by contrast, is an eclectic combination of warm wood-and-brass accents, inundated in years of quirky accumulated relics, and often arranged in a dumbfounding labyrinth of hallways and private rooms branching off of eachother in alarmingly unpredictable ways. You could literally get lost in a legitimate pub; stone sober. And properly realized, one should never be confused for another unless the befuddled is good and thoroughly besotted. Some of my favorite pubs include Edinburgh’s King’s Wark, the Dickens Inn and the Clarence of London, the Haunch of Venison in Salisbury, Birmingham’s Old Crown, the Eagle and Child of Oxford (a favored haunt of J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis!), and the tragically shuttered “church” pub of Muswell Hill, which retained every critical aspect of the magnificent chapel it epitomized in its first life.

I duck into Sainsbury’s market. The storefront, like many venues here, is narrow but deep. I load my basket with fresh berries, quiche, Scotch eggs and cumberland sausages. Taxes here are called “VAT” for “value added tax”, but are thankfully included in the very reasonable prices. I spend 25 pounds on a full basket that would easily break sixty back home. And while many big box stores in California still lack self-service kiosks, Sainsbury’s has a row of them along the front wall. I line up in a cue that leads to both the kiosks and cashiers, happy to utilize whichever opens up first. Crowds are pretty small here, so the wait is short.

Once checked out, I load my grocery bag into my backpack and return to the street. I cross the cobblestones and turn a corner, passing ancient brick-and-mortar business fronts housing all the standard amenities, from clothing to kitchenware. The interiors look shockingly conventional by contrast, although a few retain the rustic ambiance teased by the outside. The sports store presents a particular incongruity, the neon colors of its product lines in hard disparity with the naturalistic medieval setting, particularly nestled as it is beside a cobblestone courtyard at the foot of a gargoyle-rimmed clock tower.

I’m heading for the stationary store across the street, or more accurately the local post office ensconced at the back. Far and away its best feature is that it’s open for business all days of the week; a convenience of which I take frequent advantage. Unlike the trademark blue of USPS, the British Post, known as Royal Mail, is branded a deep royal red, rendering the drop boxes posted about town a striking feature of this gothic environment. During my time here I’ve sent a fair amount of mail home and have been pleasantly surprised by the affordable rate. Unfortunately, the tracking included by default in the States is a premium service here. Delivery times are also erratic; a gift I mailed shortly before Christmas arrived within a week, but most of my other shipments were off radar for a month. One pair of parcels shipped together arrived a week apart. Even more frustrating is that if anyone back home sends me a gift, I’m charged to accept anything valued above ~30 pounds. This, as I understand, is essentially an import tax gone rogue. It’s a royal pain in the Scottish arse to pay for your presents.

I turn right onto the sidewalk as I leave the venue. Behind me, a band of bagpipers are playing on the grounds of Madras college. Bagpipes, like the violin, may be an instrument of torture in the hands of the unskilled, but become something extraordinary in more able ones. Like much of Scotland, the sound of the pipes carry an ethereal, primeval quality, as though born from the depths of the earth, itself. This afforded me a shock when I discovered how adaptable they are to contemporary music. “Bag Rock” is a thing.

The air is getting crisp so I think I’m due for an ice cream. Everyone loves ice cream, but none so devotedly as the Scots. These people will swim in the ocean in thirty degree weather, and eat ice cream in the snow. I stroll down South street toward The Pends and make a pit stop at Jannettas Gelateria to settle a craving for Sea Salt Chocolate. Cone in hand, I tarry in the cloisters having been taught by the cats never to waste a sunbeam. Then I turn a ten minute walk into forty searching the tide’s latest offerings.

Finally I cross the threshold of my homestead to deposit my groceries. A slip of paper beneath the mail slot informs me that Amazon has entrusted a delivery to one of my neighbors. This is an oddity of Scottish Amazon that I’ve never seen in the States. I don’t normally interact with the neighbors, but I’m beginning to make their inadvertent acquaintance thanks to this neighborly policy misfiled from some earlier era. A knock once caught me just out of the shower and I greeted an elderly neighbor in only my robe. She chuckled, “That’s just the state I was in when they delivered this!” as she gave me my parcel. Unfortunately I have no time to harass the neighbors just now, as I’m due at the doctor’s. I head out and up the road to the corner bus stop, where I pay a pound to deliver myself the mile and a half to the clinic.

I enter the hospital and turn right, facing a mounted touch-screen just inside the door where I plug in my birthdate and surname to check in. There’s no line, and no membership card required. I’m assigned to a doctor on duty, and head to my appointed waiting area down the hall. The waiting area is typical, with a cluster of chairs and an assortment of medical paraphernalia the only augmentation to the austere decor.

I have just enough time to strip off my scarf and jacket when a man calls my name. He leads me down a conventional hospital corridor as I wonder whether I’m in the presence of the doctor or the doctor’s assistant. Standard protocol as I’m accustomed to it in the States calls for a nurse to take all the vitals – weight, blood pressure, temperature – before admitting you to a small room and directing you to a padded recliner wrapped in a coffee filter before detailing the cause for your visit. At which point they will leave you waiting another fifteen minutes for the doctor, who will ask you to repeat yourself.

I follow my mystery man into an exam room which looks indistinguishable from any other I’ve known, barring that this room is twice the size of most and boasts a full-size desk in the corner. The coffee-filter recliner is present, but I’m directed to take the chair caddy-corner to his own, allowing us to speak eye-to-eye. He introduces himself as my doctor and doesn’t take my vitals, but listens patiently as I explain my concerns. He makes inquiries and, with permission, examines the rash around my eyebrow that I’ve come about, before offering some suggestions. He’s unhurried and attentive, but the conversation wraps in under fifteen minutes. With my agreement on a course of treatment, he types up a list and prints out a prescription on the spot, offering it to me with the advise that I can take it to any pharmacy to be filled. No need to worry about who accepts what insurance – Scotland has universal healthcare.

On my way out, I notice the route is funneling me toward the exit. Since I’ve paid nothing for the visit, I retreat back to reception and ask what I owe. The attendant looks mildly confused and asks for my birthdate to pull my file. “You’re in the system as a regular patient,” she says. “Do you usually pay for coverage?” “No,” I return, altogether untruthfully. “I just wanted to be sure.” I walk out the door without ever cracking my wallet. I cross the street and turn over my prescription to the first pharmacist I encounter. Minutes later he places a small paper bag in my hands and thanks me for coming in. The cash register doesn’t even get a word in. It feels unnatural to enter a venue and acquire new things, then walk out the door without trimming the waist of my wallet, but the man in the lab coat seems happy to let me go.

The afternoon now free, I decide to return home by a circuitous route. I pass the discount store, Aldi’s, on my right. They are a small box store about the size of a mini mart in the States, and their prices are unbeatable. I usually get my bulk items there, like crumpets, vegetables and cheese, along with a few signature items like garlic dough balls. I wish that my home town in the U.S. had discount grocers as well stocked as this. One novelty of the British market experience is that they do not employ baggers. At Aldi’s, the cashier rings you up and then waits for you to transfer your purchases to a nearby convenience counter where you can load them at leisure. Many stores unfortunately neglect this feature, so bagging can be a bit of a trial. Seasoned professionals streamline this process, making it seem easy, but an inexperienced bagger like myself tends to fumble it up while customers still in cue look on impatiently. I imagine most Scots have perfected the art through a lifetime of practice.

My supplies are in good standing for now, so I carry on down City Road until I arrive at Lade Braes. I stroll beneath an umbrella of rustling red, yellow and gold through which the sunlight dapples the ground, inhaling medicinal breaths of the musty damp earth. The path trickles along beside the Botanical gardens and tiptoes between homes. I study the back gates of every abode, as each bears its own unique name. Nameplates I pass pronounce the likes of Monkswood, the Red House, Ladybrand and Netherburn. Benches along the way are marked with dedications to others who have chased faeries down this path, before.

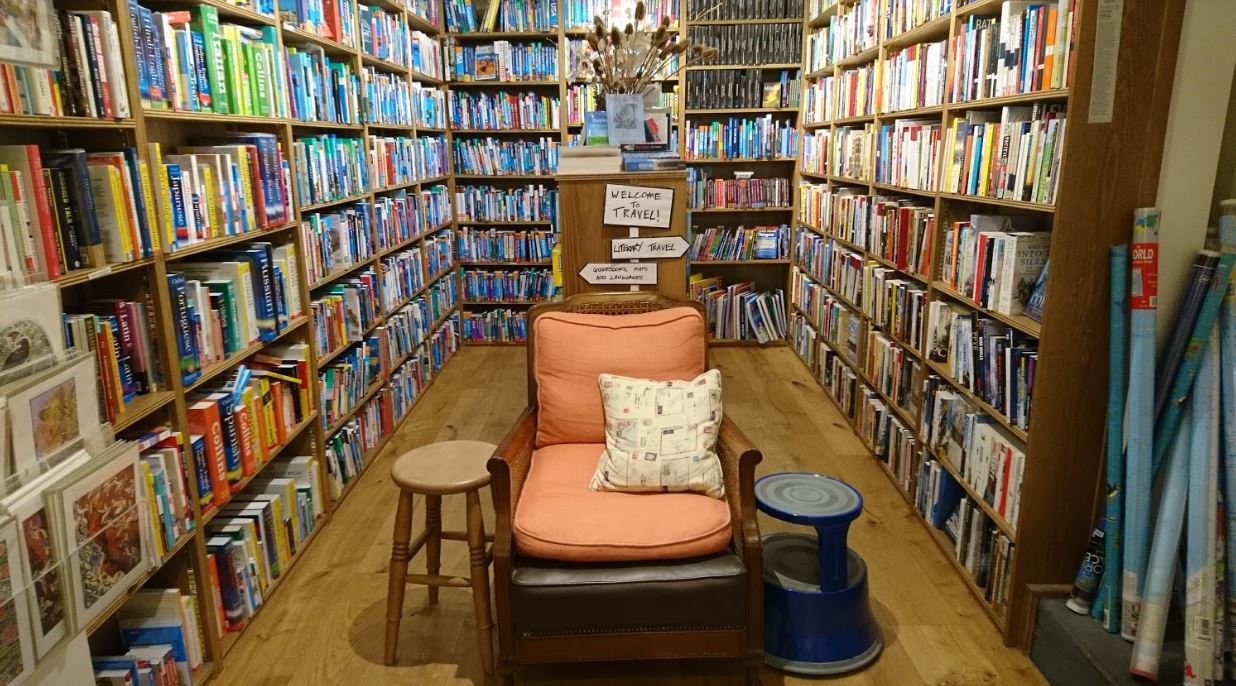

Gradually I arrive back in town and come to Topping and Co., a bookstore I discovered through the St. Andrews’ writer’s club. It is the bookseller of my dreams, or possibly a JK Rowling novel. The front room hosts an actual fireplace, and the walls are literally lined with books, with ladders set against them for ease of access. The store is narrow at the front, but branches at the back into a series of alcoves arranged by subject. I lounge in the Philosophy section and a member of staff pops his head in to ask if I fancy a complimentary cup of tea. American proprietors take note. I decline the libation, however, as the clouds are rolling in and the pub is calling.

I wander back along St. Mary’s Place and let myself through the doors of the Blue Stane. (A “stane”, google explains to me, is a stone.) Straight across from the entrance is a large, ornate bar, with wood-paneled dining rooms to either side. It’s still fairly empty at this hour, so I drape my coat over my favorite booth at the bay window before heading up to the bar to place my order. When my brother was visiting we sat at this spot and played one of the table top games the venue keeps for its patrons, but today I’m here to sample the seasonal menu: a delicacy known as “mulled wine”. It’s a wine mixed with honey and spices and served hot, resembling something like a hard apple cider.

The mulled wine warms me from the inside-out, until I’m fortified for the brisk walk home. In most of Europe, there’s no pressure to make way for other patrons, so you’re at leisure to linger. The only downside is that the servers can be just as leisurely with the bill. I manage to flag one without issue, however, and he approaches my booth with a handheld credit card reader. These are ubiquitous in Scotland, so I’m told, because consumer protections require that the customer not be parted from their card. The server thus hands over the machine and I swipe without breaking contact. The device enthusiastically pumps out a receipt which the server procures for me. I take it, nodding my gratitude. “Cheers,” I rejoin him in impeccable Scottish. I’m going to miss saying that. Or at least not getting weird looks for it.