My candid account of my experiences in Russia is laced with discoveries about why the Russian civilization is the way it is. When I walk into a produce store or any small market, I am not so focused on what will satisfy my hunger. Instead I begin to wonder why my host family is not satisfied with the Russian dairy products they buy, why the watermelon got my host brother sick for some weeks, and how those seemingly regular potatoes turned dark gray after being left out to cool.

Between the 1920-1940s, millions of people in Russia perished from hunger; specifically, during World War I and the Russian Revolution when drought and food confiscations led to famine, and later when the Soviet Union forced collectivization policies that encumbered western Siberia, the southern Urals, the Volga region, Ukraine and the Northern Caucasus, and Kazakhstan.

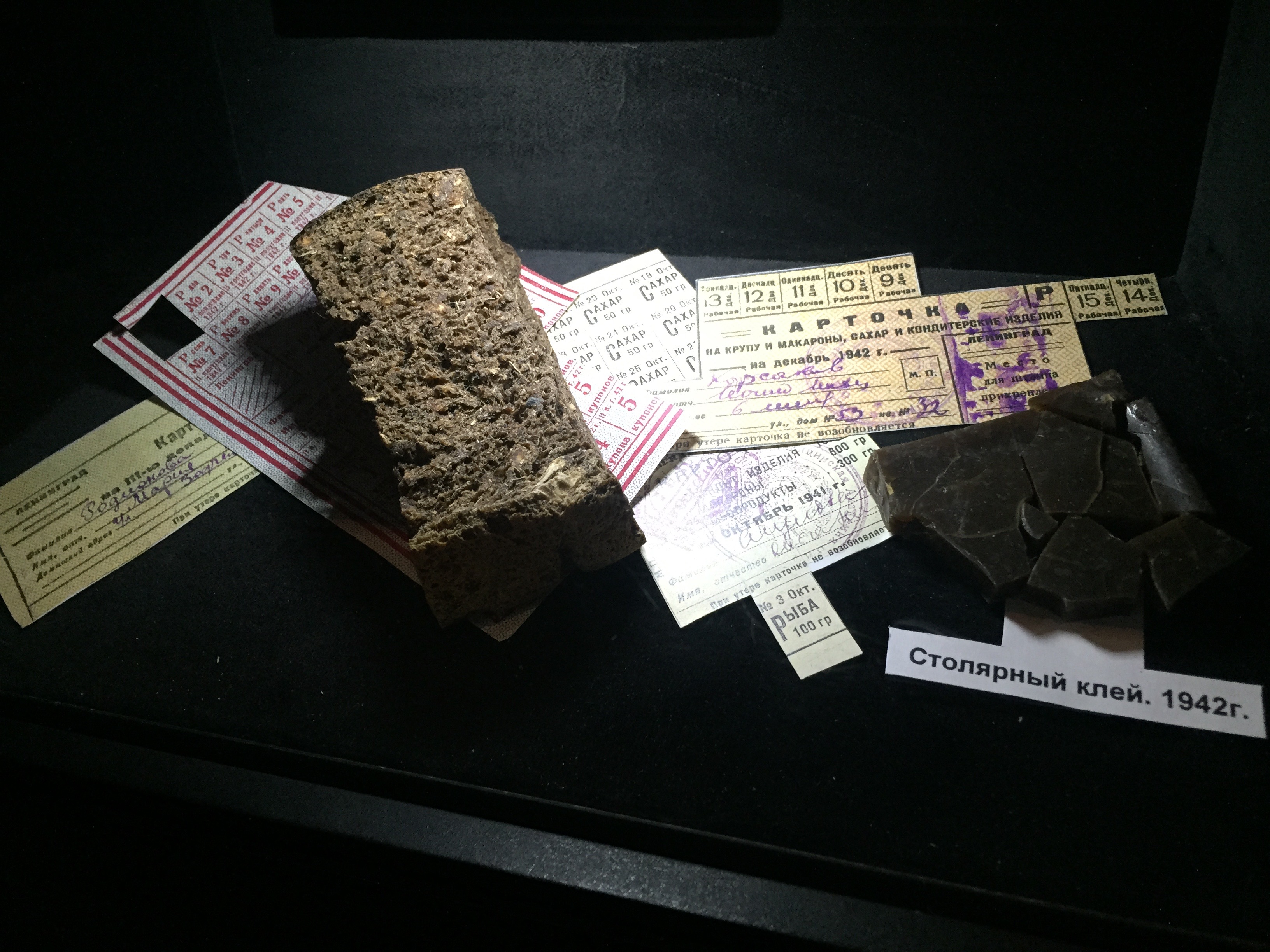

In the photo below, you will see pictured the daily ration that a person would receive during the Siege of Leningrad (usually sawdust and other fillers were added for more substance) and ration cards that contained tear-off coupons with designated monetary values. These coupons were required in addition to real money when purchasing standard goods (sugar, butter, salt, grains) and were distributed through the unions and given based on the number of members in a family.

To briefly transition from the grim mood surrounding the deficit food supply system, we will turn to humor as Russians have done throughout history. There was a joke in the Soviet Union: A boy asks his mother, “Mama, where is papa?” She responds by saying that “He is standing in the line to get coupons for the coupons.”

And we’re back. The relative progress after the collapse of the Soviet Union brought Western foods to the Russian market. At the start of Putin’s presidency, he gained significant legitimacy among his people by ensuring reliable food sources and by upgrading and expanding the types of food available.

In early August of this year, Moscow banned most Western food imports (meat, fish, dairy products, fruits, and vegetables) as retaliation to the economic sanctions on Russia by Brussels and the United States in late July. Despite criticism from many Russian households, the Russian government is standing behind its decision. As a response to some of the illegally imported food, the Kremlin destroyed such goods, a move greatly criticized during a time of increased financial and economic pressure.

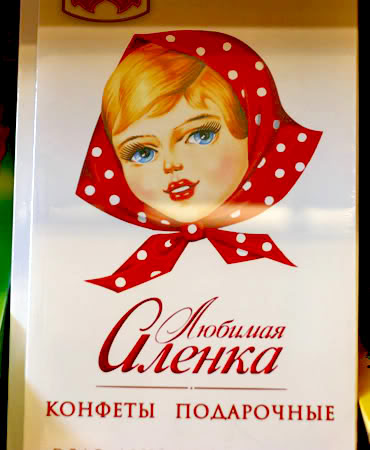

One item that can certainly be found in many markets here are the Russian chocolates, “Alyonka.” Alyonka (Russian for “Helen”) is the name of the innocent, blue-eyed, rosy-cheeked girl pictured on the wrapper. These chocolates first appeared in 1966, produced by the factory “Red October.” The factory not only survived, it thrived through war, the revolution, and strict Soviet-city planning.

Not long ago, a newer version of Alyonka appeared on the wrapper, a more made-up young girl whose bright red lips match her red headscarf. It is interesting to note that in the markets you will not find this contemporary image, instead you will find the original one.

Perhaps this puchasing decision of selecting the more folkloric child over the more made-up one is a nostalgic move. After all, the original Alyonka appeared during the Brezhnev years, a time embraced by many as a period of relative stability and prosperity. The image fit precisely with this general mood and is remembered fondly by Russians of this era, as well as by contemporary Russians.

The unsweetened reality is that many Russian households pay more for food than they should be, and more likely than not do not get the choice of adding an Alyonka Chocolate to their recycled shopping bags. Food inflation is disastrous and the ruble’s depreciation is not the only driving force. Rather, it is the direct consequence of the food embargo that inflation increased more in food sectors than in any other ones.

To refrain from ending on a negative note, I will again act as the Russians frequently do and turn to humor: As an answer to the Euro, the USA, Great Britain, and Russia decided to synchronize their currency. One pound of ruble is one dollar.