If you’ve ever studied (or traveled) abroad, then you know about culture shock. Everyone talks about it and most people, I’ve found, pretend as if it doesn’t affect them. “Oh,” they’ll tell me, “you know, I don’t find [let’s say South Africa] so different from America. I love it here.” Perhaps they are telling the truth, I don’t know, but I have my reservations. I’ve spent the last three-and-a-half years abroad, with a different home every ten months or so, and I’ve yet not to experience culture shock.

Before continuing, I do want to say that I don’t think culture shock is always immediately noticeable. For me, when I step off the plane, I don’t have this sudden moment in which I’m overcome by emotion. To be honest, the disembarkation is always a bit anticlimactic. “Really? I’ve traveled nineteen hours only to end up somewhere that looks exactly like home?” Let’s face it: airports are indistinguishable from one another.

Sometimes, the drive from the airport to my ultimate destination is more striking. Even that isn’t always the case. After all, I’m in a car on a road, usually a highway. We have all of this at home, so it’s not so exciting. Occasionally, I’ll see things that are unusual—a slum in India, a monkey in Costa Rica—but nothing that makes me feel out-of-place. For a short period of time, everything feels natural. For me, culture shock doesn’t make itself evident for quite some time.

In India, I distinctly remember the moment I fully realized I was in a different country. I was riding in a rickshaw, zipping through the streets of Bangalore, coughing because of the pollution. Tears cascaded down my face, not from sadness, but because about a dozen different spices were wafting in the air. Meanwhile, twenty or thirty children were running behind, some of them missing limbs, begging me and my friends for money. The sign at the airport didn’t do it for me; this was my welcome to India.

Nowhere else have I experienced culture shock in quite the same way, but it has nevertheless been a part of one of my trips abroad. In Lithuania, though, I find that it is a shock of a different variety. See, while much of my time is spent in the culture, much of it is also spent around Americans. I can’t even begin to explain how startling it is to realize you feel uneasiness around your own people. Having spent the vast majority of the last four years overseas, I’d forgotten some things about American society. I’d forgotten about my culture. In another post, I mentioned that I had to re-learn how to use Western utensils properly. I also had to re-learn how to respond to basic greetings, like “How are you?” This question is not an invitation to say how you actually are. Acceptable responses are “fine” and “well.” Obviously, this isn’t always the case, but we Americans have programmed such responses into our heads. They are as natural for us as breathing.

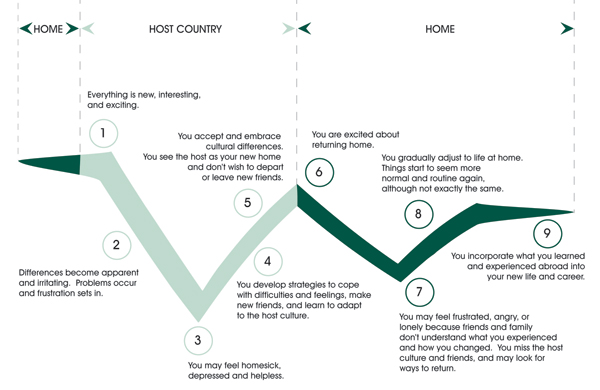

The Gilman Scholarship Program gave me a diagram (pictured below), which essentially states the nine stages of culture shock. For the most part, I agree with it, but my culture shock doesn’t match the diagram precisely. Though I have my moments of depression and homesickness, they tend to be rare and occur in bursts throughout, not Stage 3, as the diagram suggests. Moreover, most often, when it is about time to return to the United States, I don’t feel ready for it. Butterflies host a fiesta in my stomach. It doesn’t make sense, I know. Why should I be nervous going home? I guess it’s because after a year away, home doesn’t feel like home anymore. Thoughts begin to creep into my head: “What if I’ve changed? What if my friends and family have changed?” On my first return trip, when I was coming back from Costa Rica, I would wake up in the middle of the night and experience this strange sensation of loneliness. I was in my bed in the home I’d always lived with my family all in their own beds, and yet I felt completely and totally alone. I felt like the stereotypical misunderstood teenager. The feeling would eventually pass and I’d drift off into sleep, but the process would repeat itself again and again. I think it took about three months for the episodes to cease entirely.

On my first return trip, when I was coming back from Costa Rica, I would wake up in the middle of the night and experience this strange sensation of loneliness. I was in my bed in the home I’d always lived with my family all in their own beds, and yet I felt completely and totally alone. I felt like the stereotypical misunderstood teenager. The feeling would eventually pass and I’d drift off into sleep, but the process would repeat itself again and again. I think it took about three months for the episodes to cease entirely.

Neither of my return trips from China or India produced such results. I think it’s because I could mentally prepare myself. In other words, I already knew what to expect. It’s true what they say, what the study abroad orientation people warn you about—the experience changes you. And you return home, feeling like a completely different person, but nobody else seems to notice. You’ve underwent one or two or three transformational, life altering moments. You want to tell everyone about them. Then you get home and find yourself inarticulately conveying that incredible moment to a family member or friend, and you become frustrated with yourself for your inability to do so satisfactorily. These are moments that live with you, and only you, forever. No matter how many people you tell, no matter how many photographs you show them, they’ll never understand quite the way you felt at that moment in time. It’s this inability to effectively translate my experiences to others which produced my nightly episodes upon returning home.

Hopefully, this post doesn’t dissuade any potential study abroad-ers from actually going out and studying abroad; it’s certainly not meant to do that. But feelings of isolation do affect study abroad students. I don’t think we discuss them enough because they manifest themselves in the midst of feelings of confusion and excitement and busyness, but they are just as real, and affect us just as much. In fact, I almost think that the isolationist feelings are beneficial, that they serve as a reminder—this is our experience, one that (for better or worse) cannot be taken away from us.