Beunas,

Before studying abroad in Central America, I knew living in a machismo culture for the first time would be a challenge because of my strong feminist views. Machismo, an exaggerated sense of male pride to dominate females, reveals itself in everyday interactions here in Costa Rica. Feeling objectified so often here is one thing that continues to frustrate me most.

The casual sexism I’ve faced in Costa Rica has been a serious struggle for me at times. As a woman, I’ve constantly been put in positions where I feel uncomfortable because men think it’s a “compliment” to stare, blow kisses, and shout derogatory phrases at me in the street.

The moment which made me feel most upset was when I was having a conversation with a person here whom I considered to be a friend and he nonchalantly asked me my opinion on casual sex. It was particularly hurtful because it made me feel as if I was being ostensibly befriended for the sole purpose of being a sexual prospect, which my host mother and a local girl friend of mine here both explained to me is very common in this culture.

Posters displayed around campus to remind students of what sexual harassment is.

Another poster displayed around campus to remind students unwanted physical contact is a form of sexual violence.

As a passionate feminist, I struggle with identifying the appropriate response to this casual sexism. As a person coming from another country, is it right to “look down” upon what has been traditionally the norm for this culture? Or does that make me ethnocentric? Here’s what I have come to conclude: It’s undignified to cause any person to feel uncomfortable or unsafe. Furthermore, treating other people like objects can be a step toward treating someone with violence, which is ultimately dangerous to a community. While I can understand that people in Costa Rica have been raised to think a certain way from childhood, I believe there is room for progress in treating all genders with dignity. Promoting change starts with understanding why culture in Costa Rica is permissive to treating women like objects.

Akin to culture in the United States, Costa Rica rears children with gender binary structures and terminology. Many words in Spanish can perpetuate shame and stereotypes associated with femininity. A prime example is the word esposa which directly translates to English as “wife,” but in Spanish is used to also refer to handcuffs. Furthermore, Spanish words can be used to undermine the power of femininity, such as consistently using the masculine noun to prevail in instances of referencing a group of people, whether they are of mixed gender or solely one. Niño prevails when referring to all children, though the feminine noun niñas is not considered socially acceptable to refer to all children, unless it is a specific group of children who all identify as girls. The same is true for the words chicos and chicas, and ticos and ticas. In fact, if referring to a group of mixed gendered people with the feminine form, some may take offense to it. The same is true in the United States, where people typically refer to a group of people as “guys,” but it would be considered undignified to refer to a group of men as “girls.” This is an example of how words can teach people to refer to women as of lesser value and thus perpetuate discrimination.

Furthermore, Costa Rica puts a lot of emphasis on the value of feminine beauty. I found it very interesting that my first few lessons in Spanish had so many gender binary descriptions. For instance, many of the basic phrases which addressed women commented on their appearance rather than intelligence or any other quality which suggests an accomplishment. Interestingly, I did not learn how to “compliment” a man on his beauty until a week after, when I was corrected after calling a man bonito.

One of my feminist friends holding up a picture which displays common sexist attitudes. It translates as “That new haircut makes you look more old.”

This is spray painted on a wall in Heredia Central. Abortion is illegal in Costa Rica. In 2007, it was reported that abortions secretly rose to 22.3 for every 1,000 women from 10.6 for every 1,000 women. Annually, this calculates to an estimation of 27,000 abortions being performed illegally in Costa Rica annually.

To some, deconstructing casual sexism may seem trivial. However, the consequences of not addressing such a serious issue leads to everyday violence. Quite recently, The Tico Times reported about a man who was stabbed to death because he was attempting to raise awareness about the street harassment woman typically face in this culture. The murdered victim was filming another man who was looking up the skirts of women with a mirror on his shoe.

Costa Rica has taken progressive steps toward addressing serious gender issues. During a national soccer game, the scoreboard displayed the number of domestic violence calls the police received throughout the time of the game. Because soccer is to Costa Rica what American football is to the United States, thousands of people watched and considered the fact that sporting events are a prime time for domestic violence. Working three years with Crisis Intervention of Houston as a crisis hotline counselor, Super Bowl Sunday in the U.S. was cited as the day where the most domestic violence cases are consecutively reported. For that reason alone, it could be impactful if major sporting events in the U.S. could have something similarly displayed on the scoreboards. Costa Rica has also promoted laws which are meant to punish perpetrators of domestic violence. For instance, men who commit violence against their partners may not be allowed to keep a gun in the home or will be ordered to temporarily relocate while still providing financial support to his family. Additionally, the National Institute of Women in Costa Rica has established programs and shelter for gender-based violence. According to the Costa Rican Department of Police Intelligence, during the first three months of 2012 alone, law enforcement received an average of 222 reports of domestic violence per day. This amounted to a total of 19,975 domestic violence cases in all of 2012 – 5,195 more cases than were reported in the first few months of 2011.

During a nationally aired soccer game, Costa Rica displayed a third score to tally the numbers of police reported domestic violence cases. Throughout this game, this number rose to 25.

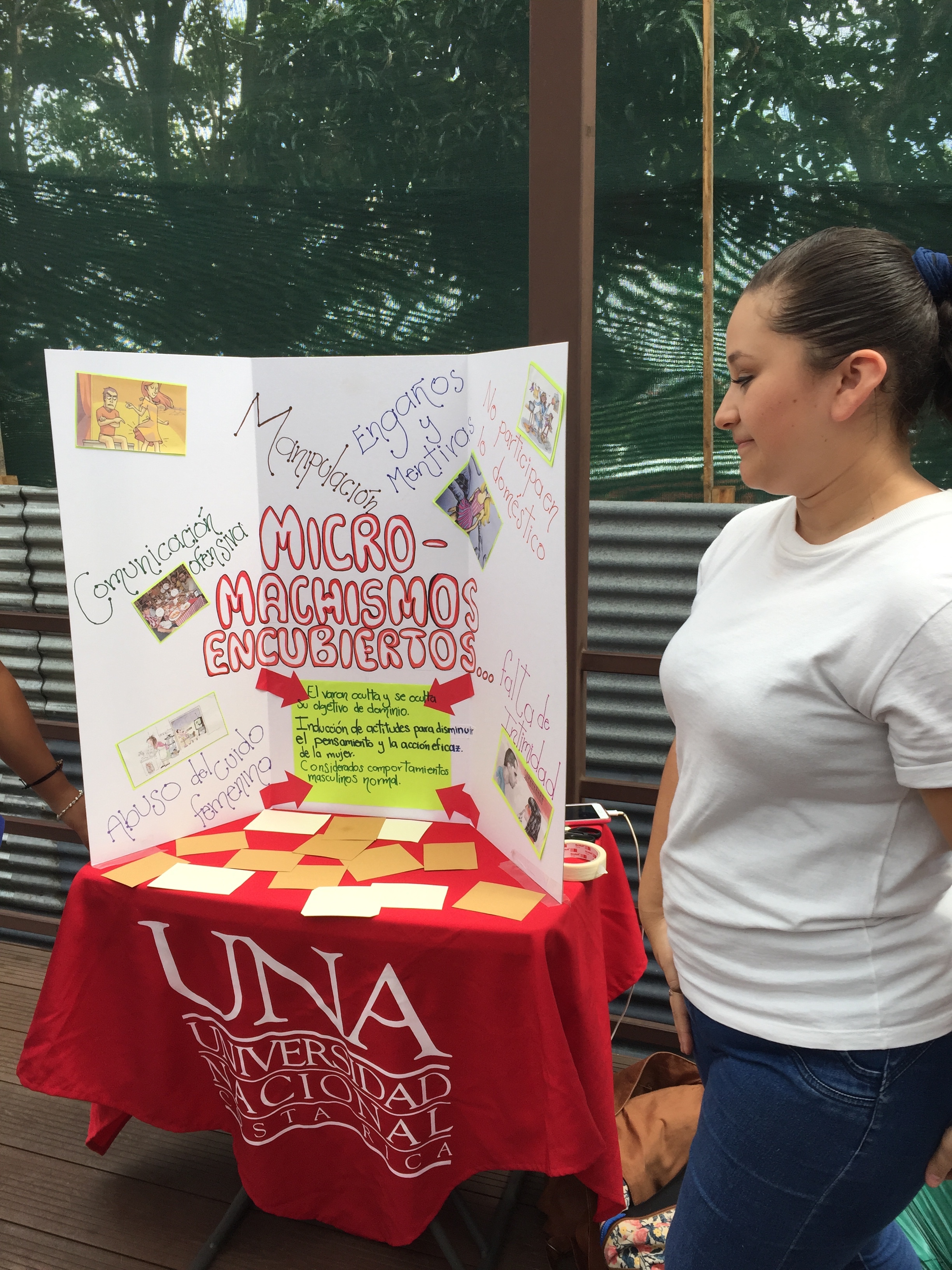

Universidad Nacional de Costa Rica has been spreading awareness about sexual harassment and the harmfulness of machismo culture with posters and presentations all throughout campus. I took photos of some of the displays in hopes of bringing these ideas back to my home university.

Posters displayed around campus to remind students of what sexual harassment is.

Currently, a big debate in Costa Rica surrounds Banco de Costa Rica (Costa Rica Bank), and their new women-only bank called Banca Kristal. Banca Kristal‘s slogan in the newly released advertisement is ninguna mujer es complicada, which translates as “nothing about women is complicated.” This advertisement can be found all around San Jose and Heredia. Though the idea for the bank is to empower women by giving them financial access, particularly those who face economic challenges, there is much criticism of the bank from local feminists because some argue it perpetuates stereotypical roles of women. For instance, the bank is all pink inside and outside, and offers women special savings accounts for beauty products, and according to The Tico Times, also distributes free clutch handbags to its clients. The advertisements, which can be seen on billboards near my home and during advertisements at the local cinema, all feature young and conventionally beautiful women. If this bank is meant to empower women by providing tools for economic stability, why is there so much emphasis on selling an image of beauty? How will a glamour advertisement help a community full of women refugees from Nicaragua recognize this bank as source of help? We shall see what the future has in store for this bank and how it impacts the community.

The giant billboard in front of my neighborhood which translates as “Nothing about women is complicated.” This is an advertisement for Banca Kristal. Does this ad challenge or perpetuate sexism?

Let’s hope this year brings more awareness about gender issues so that we can generate change!

Sincerely,

Alexandria