A couple days ago we were talking about the impending end of our program and one of the other girls asked me if I was homesick. I think I surprised both of us with my answer because I said no. I said that since I go to college on the other side of the country from my family, I already don’t see them during a semester so I’m not seeing any less of them. And with Facebook and Skype I’m in contact with them just as much if not more so while I’m here than when I’m in Boston. The only difference is that in Boston I can pick up a phone at any time during the day and make a call to hear my mom and dad’s voices. I can’t do that here in part due to the six hour time difference and in part due to the expense of international calling. Instead I use chat and video chat and they follow this blog to hear about the day to day and special experiences that are just too long and involved to share during a quick conversation between classes.

That’s not to say I don’t miss home. I do. I miss being able to cook whatever and whenever I want. I miss the ability to walk out into the streets and be able to communicate fluently with every person I see.

To know exactly what is expected and what is appropriate and what is not is something that we learn during childhood. In this full immersion study abroad I have become a child all over again relearning how to interact with my surroundings.

Unlike most children however, I have even less of a vocabulary than a four year old learning right from wrong in preschool. I also have my own preconceived notions that I need to overcome and evaluate. Notions such as the appropriate reaction to a guy who cat calls me when I’m walking down the street being to laugh it off, make eye contact, and keep walking. In Morocco you are supposed to stay quiet, eye contact is seen as an invitation, and you definitely keep walking and don’t react.

Everyone misses something or someone at some point in their lives. For me, homesickness has always been a specter of overwhelming anxiety and a desperate urge just to return to what is familiar and known and therefore safe. I have felt this before on other international experiences. I felt this on my first day of college orientation when I was on my own in a crowd of four hundred other students on the other side of the country from my family and everything seemed to be happening at warp speed and I had no clue how to respond to any of the people around me, where to go, what to say, or who anybody was. I broke down in tears and was on the verge of returning to my dorm room to hide and curl up with a book and my phone when one of the older students saw me and came over to give me a hug and guide me through the process making sure to give me her phone number and introducing me to other students who were in a similar situation.

I had a professor once who told us to try to see the world through a child’s eyes. She said that children see everything around them as bright and new. Even their own hands and feet are a surprise to them. I have been forced to do that this semester. Living in a home without western plumbing and needing to go to the public baths once a week in order to thoroughly wash reacquainted me with my body in unexpected ways. Being unable to communicate with words and facing the difficulty of pronouncing those words that I should remember forces me to relearn the non-verbal communication that we all take for granted and may not even notice as adults. In a culture that was more similar or in more similar surroundings, this challenge of communication might have been seen as frustrating or embarrassing as I can’t even talk about basic needs. However, here where everything is so different, it seems new even as I walk through doors that have been standing for almost 1,000 years. There is no ability to compare the situations I find myself in here with the situations I face at home and so when I don’t know how to react, there is no anxiety. There is no safety net to fall back into, nowhere to escape to and most importantly when I fall I have to get up and keep going. People here are understanding and hospitable. If I fail, they will point out how and why but they won’t judge me as bad or wrong, simply different.

The last item on the packing list that SIT sent to us before our departure for Morocco was a sense of humor. This is the lightest item in your suitcase and the most important one. The larger your sense of humor, the better. After all, it needs to be big enough to cover you and all your situations, not just the external situations of others. So long as I can laugh at myself, laugh with others, then I know I’ll be just fine!

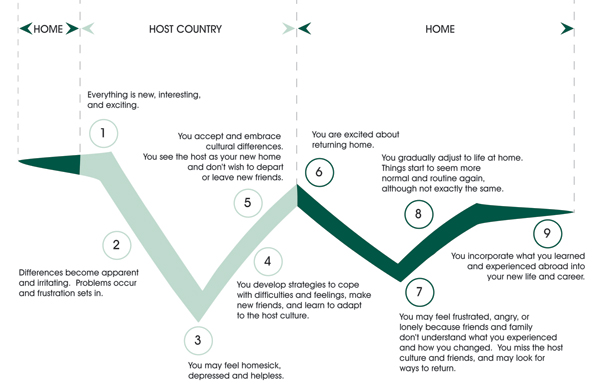

*Note: this graph on Culture-Shock shows the stages that many of our study abroad participants experience. It seems like Danielle has embraced the cultural differences (stage 5), so it may be hard for her to leave Morocco when the program finally ends.